On Active Learning in Software Engineering

I’ve read 2 papers recently (references) about using active learning to improve classification for software engineering.

Active Learning is the idea that, if we have a feature space with instances, for the classification task of labeling an instance either “A” or “B”, there are clumps of points that clearly are As, and another clump that are clearly Bs. In between, however, the boundary is unclear. Some instances will be equidistant from both centers of mass, and the classifier will struggle to properly classify it. Active Learning (AL) quite simply picks what are hopefully the “most useful” (for improving the classifier) points for human labeling, which reduces the amount of (possibly) redundant labeling humans have to do (since the labeling time is the most costly part of creating a classifier).

It turns out that so far this active learning approach for software data is not too successful. I think there are 2 main reasons.

1) We don’t have much data. Classifiers do better when they see more instances. In the 2 studies I read, the number of unclassified instances was measured in tens of thousands. Contrast this with most image recognition or information retrieval applications, which have orders of magnitude more training data. In the case of the ImageNet context, they also label substantially more instances (e.g. 150,000 labeled with 10 labels).

2) More importantly, I think the task is fundamentally difficult. The Borg paper makes this clear; when human raters themselves cannot agree on a label, it probably won’t work any better with active learning. I think this is because some problems have fuzzy label boundaries for non-core feature reasons, while many software concepts are innately (ontologically) unclear. Think about labeling photos of house numbers. I’m pretty confident that any two humans would agree that instance X is a house number. We have clear and simple criteria for what a “number” is (intensionally and extensionally). The reason the classifier struggles is because of non-intensional properties of the data itself: perhaps a tree obscures the top of the 1, or a shadow is partly on the lower digits. In software data, that problem exists as well (e.g. someone talking about an old version of Rails). But for labeling an utterance as technical debt, or a performance bug, or a usability concern, there seem to be broad disagreements on the core discriminating features. If we talk about paradigms like distributed computing, is that an “architectural” discussion? What about a bug that results from not understanding an RPC service?

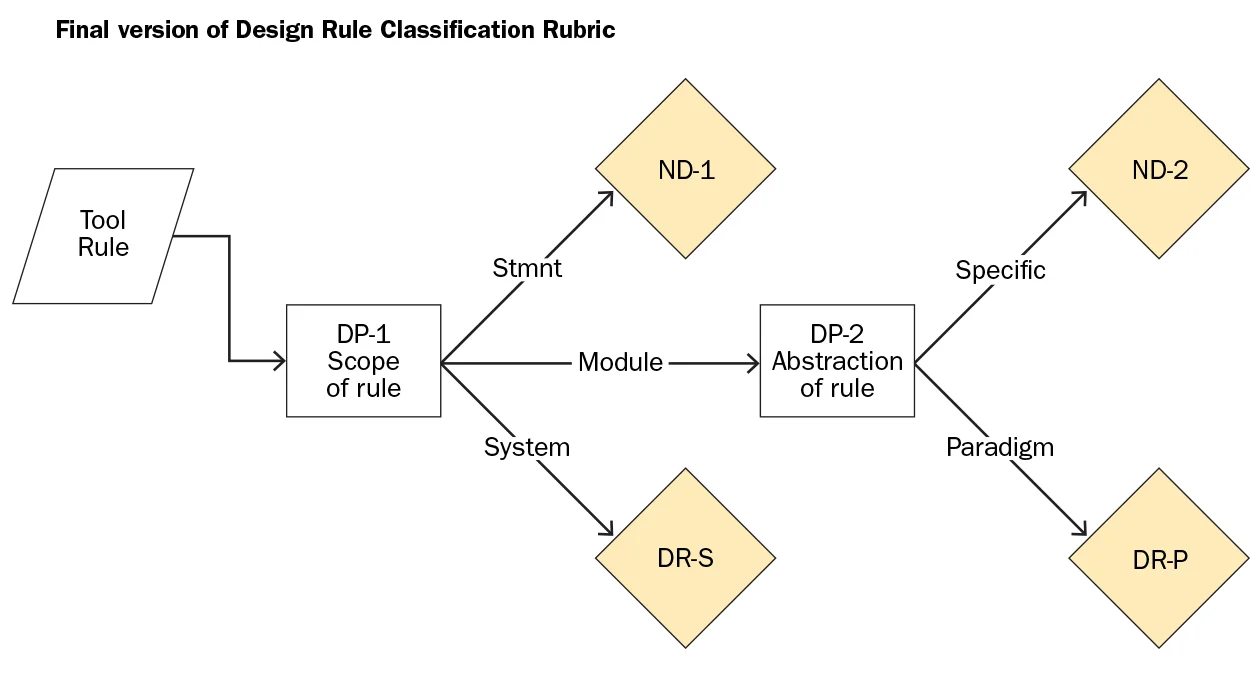

We’ve looked at some of this in our latest research on design rules. We found that while a majority of static analysis/code checker rules can be clearly distinguished as either design or not, there remains this stubborn middle tier that resist easy categorization. We think you can still make progress (after all, these rules may not even fire on your project). But it would be satisfying to have a more repeatable analysis.

The conclusion of the Borg paper really seems useful for future work here. One, they say that the AL approach helps to pull out controversial instances, that then help build rater consensus. Two, using bootstrapping with more positive examples helps the AL improve its accuracy (in other words, there is still benefit to grinding out the labels manually – no free lunch, sorry!).

References

- N. Van Houdnos, S. Moon, D. French, Brian Lindauer, P. Jansen, J. Carbonell, C. Hines, W. Casey. “Human-Computer Decision Systems for Cybersecurity”, Presentation. https://resources.sei.cmu.edu/asset_files/Presentation/2016_017_001_474277.pdf

- Borg, M., Lennerstad, I., Ros, R., Bjarnasson, E. “On Using Active Learning and Self-Training When Mining Performance Discussions on Stack Overflow”, arXiv:1705.02395v1. Preprint of paper accepted for the Proc. of the 21st International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, 2017.